BY LILY LYNCH MAGAZINE MARCH 31, 2014

The Turkish Prime Minister’s son-in-law is the CEO of a company that has enjoyed a cozy relationship with eccentric dictators in Central Asia and some of the most powerful leaders in the Balkans.

The wedding of Esra Erdogan and Berat Albayrak was designed to showcase Turkey as the “bridge between the West and the Islamic world”. Though the hijab was still banned in public institutions, and scorned by Istanbul’s secular elite, the bride wore a white headscarf draped in translucent jewels. About 7,000 guests flew in from various points around the globe to attend the extravagant event, which was held inside the same Istanbul convention center where the heavily protested 2004 NATO summit had taken place just a few days earlier.

Security surrounding the high-profile nuptials was kept deliberately tight, with some 5,000 police officers dispatched to patrol the streets, and snipers assigned to rooftop positions across the city. Safety measures alone reportedly cost 50 billion Turkish lira.

The ceremony’s four official witnesses were all foreign dignitaries: King Abdullah II of Jordan, former Pakistani President General Pervez Musharraf, and the prime ministers of Greece and Romania.

Silvio Berlusconi was unable to attend, but sent his regrets along with a Versace vase.

Esra Erdogan marries Berat Albayrak, soon-to-be CEO of Calik Holdings, in July 2004.

The choice to include two Muslims and two Orthodox Christians in the marital rites was a deliberate one. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan had only been in office for about four months at the time, and was eager to use his daughter’s vows to remind the world about Turkey’s historical prominence in the region. Of course, this was when Erdogan was eager to join the EU, and still cared about his standing with the “international community”. He even arranged to have a film crew from CNN Turk broadcast the entire wedding on live television.

Ahmet Calik, one of the richest men in Turkey, stood beside Erdogan for the duration of the ceremony.

The baby-faced groom was Berat Albayrak, a recent graduate of New York’s Pace University and the son of a conservative journalist who had been a close friend of Erdogan’s since 1980. Though Berat was just 23 years old when he married the prime minister’s eldest daughter, he was fast-tracked to a prestigious position with Ahmet Calik’s powerful Turkish conglomerate Calik Holding, which has extensive investments in the Balkans and Central Asia. Within a few years, he was its CEO.

Calik and Erdogan.

“We will wipe out Twitter,” Erdogan promised at a recent campaign rally in the industrial city of Bursa. “I don’t care what the international community says. They will see the Turkish republic’s strength.”

The Twitter blackout was reportedly a response to rumors that audio recordings linking Erdogan to alleged corruption had surfaced on the site. It was the latest episode in a sordid corruption scandal that has dominated Turkey since dawn broke on December 17.

This winter, key cabinet ministers resigned, and their adult children were taken into police custody. Numerous members of the prime minister’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) were arrested, along with the head of the state-owned financial institution Halkbank. Police were said to have found shoe boxes stuffed with $4.5 million in cash inside the bank director’s home. Soon a grainy VHS-quality sex tape started circulating online, which appeared to star the pious prime minister’s businessman brother, Mustafa Erdogan, engaged in an act of adultery.

Erdogan’s response has been characteristically defiant. He’s fought back by attacking the internet and purging the police force of thousands of officers. The prime minister maintains that he’s only trying to protect the country from another coup. (Turkey has endured four in recent memory: in 1960, 1971, 1980, and 1997). For now, it seems Erdogan has emerged victorious.

Erdogan gives a speech to AKP members in Ankara, December 2013.

The prime minister and others in his orbit say members of a secretive Islamic religious order known as the Gulen movement have methodically infiltrated Turkey’s judiciary and police force as part of a plan to overthrow Erdogan from the inside, and the government and the cemaat (religious movement) have been engaged in a very public media war for months.

Fethullah Gulen is an enigmatic diabetic who has lived in self-imposed exile in rural Pennsylvania since 1999. In a Foreign Policy poll conducted in 2008, he was voted “the most influential intellectual in the world”.

But Erdogan’s AKP scored a significant victory in Sunday’s nationwide local elections, which seems to indicate that Gulen’s allegations of widespread graft have done little to dent the prime minister’s popularity with much of the electorate.

It’s easy to see how Gulen may have overestimated the persuasive powers of his own influence: His disciples have opened some 1,000 schools in over 140 different countries, and established media outlets, including Zaman — the newspaper with the widest circulation in Turkey.

Until relatively recently, the Gulenists were the AKP’s allies in the fight to challenge Turkey’s state-sponsored secularism and powerful army. In Gulen: The Ambiguous Politics of Market Islam

, which was released in August, Joshua D. Hendrick described the Gulen movement as the AKP’s “most important collective partner”. Little has been said about how the Gulen movement, which followers call Hizmet or service, may have benefited from a decade spent collaborating with Erdogan’s government. Hendrick notes that Gulen-affiliated institutions “received favors” from AKP bureaucrats, and that companies operated by Gulen’s followers “received tenders with the help of AKP policies”.

Many ethically questionable activities involving both Calik Holdings — the company headed by Erdogan’s son-in-law — and the Gulen movement extend far beyond Turkey’s contemporary borders, because Erdogan and Gulen share something else: a belief that modern Turkey is the continuation of the Ottoman Empire and the center of a collective civilization that stretches from Central Asia all the way to the Balkans.

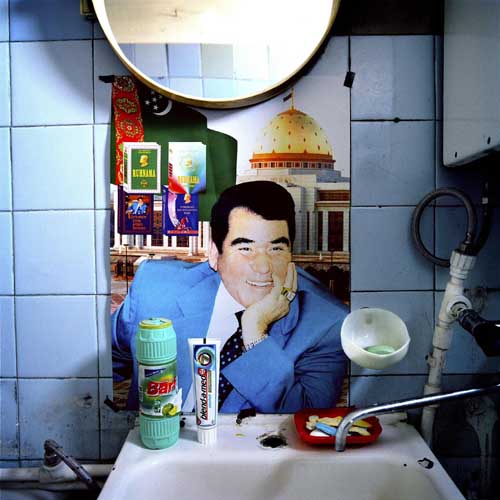

Turkmenbashi, the “Father of all Turkmens” in a 2007 World Press Photo Contest-winning image. (Photo credit: REUTERS/Nicolas Righetti/Rezo/Handout, one time usage permitted).

Ahmet Calik, the billionaire businessman who stood beside a teary Erdogan at Esra and Berat’s wedding, enjoyed a bizarre and almost intimate relationship with Saparmurat Atayevich Niyazov, better known as Turkmenbashi, the father of all Turkmens. Niyazov ruled Turkmenistan from 1985 until his death in 2006, and during that time, he cultivated one of the most eccentric personality cults in modern history. The list of things he banned was long: car stereos, ballet, long hair, make-up on newscasters, libraries outside of the capital, recorded music at weddings, opera, the death penalty, and video games. He also established a Ministry of Fairness.

All the while, human rights were non-existent; torture, imprisonment and forced psychiatric treatment were used to keep dissidents in line; and the country was one of the most repressive in the world. Ahmet Calik, who made Erdogan’s son-in-law his CEO, was the dictator’s closest advisor and confidante.

Erdogan’s son-in-law Berat Albayrak and billionaire Ahmet Calik.

Calik is a native son of Malatya, one of the fast-growing Anatolian Tiger cities credited with driving the Turkish economy. A middle-aged man with a well-trimmed mustache and an affinity for silk ties, Calik has been called the Gulen movement’s “star entrepreneur”. In US diplomatic cables, he’s also been described as “close to AKP and the prime minister himself”. As of last year, he had an estimated net worth of $1.7 billion.

He also had a knack for exploiting Niyazov’s delusions of grandeur for his own financial gain.

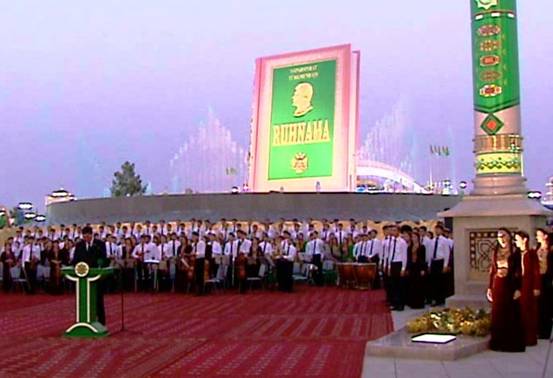

President Niyazov wrote a semi-autobiographical “holy book” called the Ruhnama in 2001 that schoolchildren were forced to memorize, and which eventually supplanted normal education in Turkmenistan altogether.

“I sacrifice my life and my flesh to you; if I do the slightest harm to you, let my tongue dry and fall off like a leaf,” a group of Turkmen schoolchildren recite from the Ruhnama in one unsettling scene from Arto Halonen’s 2007 documentary, The Shadow of the Holy Book.

There’s a massive, mechanized statue of the Ruhnama towering over the capital city of Ashgabat — a birthday gift to the dictator from Ahmet Calik. Every night at exactly 8 pm, the cover of the book opens and an audio recording blares the Ruhnama’s verses, while a colorful video of Turkmenbashi’s face is projected onto an enormous blank page.

Calik was the first foreign businessman to understand that translating the Ruhnama into a new language was the most effective means of obtaining lucrative business contracts in Turkmenistan. Hendrick claims that a “senior-level aristocrat” in the Gulen movement’s hierarchy prepared a Turkish translation of the so-called “Book of the Soul”, which Calik then presented to Turkmenbashi at an official ceremony.

Statue of the Ruhnama in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. A birthday gift from Calik to Turkmenbashi.

Niyazov famously renamed the months of the year after members of his own family, but few know this was actually Calik’s idea. The eccentric cruelties of his dictatorship were seemingly infinite:

He used the enormous wealth generated by Turkmenistan’s production of 70 billion cubic meters of natural gas each year to experiment with the limits of his country’s extreme climate. He demanded that an ice palace be built in the middle of the Karakum desert — the hottest place in Central Asia. Though summer temperatures in the area often exceed 50 degrees celsius (about 122 degrees fahrenheit), he also insisted that desert ice park include a flock of penguins. (A U.S. diplomatic cablesays Calik’s company built the ice palace).

An International Crisis Group report on Turkmenistan for the year 2004 mentions Calik’s name numerous times. He was and remains the biggest foreign investor in Turkmenistan.

Calik’s own operations in the country have included textile factories that produce denim for H&M, Levi’s, and Calvin Klein using child labor, and a number of outlandish construction projects in Ashgabat, including the Great Saparmurat Turkmenbashi Cultural Center, and the Independence monument, which looks like a gilded missile.

Calik is suspected of “financial machinations” and “abuse of his access to Turkmenbashi”. He was granted full Turkmen citizenship in the 1990s, and served as Minister of Textiles. Turkmen opposition leaders often complained that Calik exercised an “unhealthy” level of control over Turkmenistan’s internal affairs.

Calik at a ribbon cutting ceremony with Niyazov (Turkmenbashi).

In addition, Calik supported the publication and distribution of a new Turkmen-language version of Zaman, the Gulen-affiliated newspaper. Soon, there were local editions of Zaman being published in the Central Asian capitals of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Then in 2003, Niyazov abruptly announced that Russian should no longer be a language of instruction in schools. By the end of Niyazov’s life, only one Russian-language school remained, and the country’s only French and German schools were also closed. “The Turkmen government virtually prohibited internationally sponsored curricular reform altogether,” Erika Dailey and Iveta Silova, two prominent researchers on Central Asia, wrote.

But Turkish schools, operated by members of the Gulen movement, managed to thrive under the oppressive and bizarre dictatorship. In fact, there were 16 Gulen-affiliated “Turkmen-Turkish” schools scattered across Turkmenistan by the start of the 2006-2007 school year.

Most agree that “Gulen-affiliated” Turkish schools blossomed under Niyazov’s repressive dictatorship due in large part to Ahmet Calik. “The Gulen community is very active in Turkmenistan because its members served as advisors to President Niyazov himself (the adviser on energy issues and the deputy minister of textiles, Ahmet Calik),” Dailey and Silova explained. “In addition, the Gulen community is known for its supportive attitude toward the authoritarian government of Turkmenistan.”

Parents needed to pay high fees to send their children to the schools, meaning Gulenist institutions, spread throughout post-Soviet Central Asia in the name of “Turkic brotherhood”, largely served the elite. The annual tuition for a spot at a Gulen-affiliated school in Turkmenistan was roughly $1,000 in the early 2000s, while GDP per capita was only about $5,000.

Turkmenbashi dropped dead of myocardial infarction in December 2006, leaving control of the country to his dentist, Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov. This successor and strange Niyazov doppelganger made Calik uneasy about the security of his own business dealings in Turkmenistan, even though the two had lived as neighbors in the same Ashgabat highrise built by Calik’s own construction firm for years. According to diplomatic cables, Calik had an emotional four-hour dinner in Istanbul with American Chargé d’affaires Richard Hoagland in September 2007 during which he lamented that the late Turkmenbashi had “treated him like a son”.

Bulent Kilic/AFP/Getty Images

Protesters with placards of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the US-based Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen during a demonstration against corruption, Istanbul, December 25, 2013. The text on the placards says ‘We will cast them down!’

Two pilots who are flying an airplane together start punching each other in the cockpit. One ejects those members of the crew whom he believes to be close to his rival; the other screams that his copilot isn’t a pilot at all, but a thief. At that moment, the plane spins out of control and swiftly loses height, while the passengers look on in panic.

These are lines from a recent newspaper column by Can Dündar, a Turkish journalist, and I can think of no clearer aid to understanding the perverse, avoidable, almost cartoonish confrontation that has engulfed Turkey since last December, and that threatens to undo the political and economic gains of the past decade.

The parties to the confrontation are the prime minister, sixty-year-old Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and a Turkish divine, Fethullah Gülen, thirteen years his senior. Erdoğan leads the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), and works in the political hurly-burly of Ankara, the country’s capital. Gülen is Turkey’s best-known preacher and moral didact. He lives in seclusion in Pennsylvania, reportedly in poor health (he has heart trouble). Gülen presides loosely but unmistakably over an empire of schools, businesses, and networks of sympathizers.

It is this empire that Erdoğan now depicts as a “parallel state” to the one he was elected to run, and he has undertaken to eliminate it. The feud began in earnest last December and has had a remarkably destructive effect. Many of Gülen’s followers work within the government and have had much power. Now large parts of the civil service have been eviscerated, much of the media has been reduced to unthinking carriers of politically motivated revelation and innuendo, and the economy has slowed down after a decade of strong growth. The Turkish miracle is over.

Erdoğan’s AKP government and the Gülen movement share a modernizing Islamist ideology, and although relations between them have been deteriorating for some time, before the current crisis it was possible to be affiliated with both. Coexistence ended abruptly on December 17, when more than fifty pro-AKP figures, including the head of Halkbank, a state-owned bank, a construction magnate, and the sons of three cabinet ministers, were taken in for questioning by prosecutors who are regarded as Gülen’s men.

The raids were allegedly carried out by Gülenist policemen and they were given much attention by newspapers and TV stations with a similar pro-Gülen bent. Allegations that the well-connected detainees were guilty of bribery, smuggling, and other crooked activities were tweeted and retweeted in a frenzy of condemnation; the Gülenist assault from within the government as well as outside it had been well planned. Incriminating evidence was indeed uncovered, including some $4.5 million kept in shoeboxes in the home of the Halkbank chief executive, along with indications of payments to ministers. It soon emerged that a second phase of the same investigation would touch the prime minister’s son.

The speed and vigor of Erdoğan’s reaction to these events indicate that he regarded them as a precursor to his own destruction. He immediately began clearing out compromised or potentially traitorous members of his entourage, and within a few days had replaced half his cabinet, including those members whose sons had been taken into custody. The purge has spread to far points of the civil service. As part of Erdoğan’s campaign against the influence of Gülen, thousands of policemen have been moved from their posts, as well as senior prosecutors involved in the corruption case, and bureaucrats associated with the departed ministers have also been shuffled or dismissed.

Earlier in February the government began investigating Gülenist police officers on suspicion of “forming an illegal organization within the state.” Erdoğan stopped the judicial investigations and instead took direct action. Two months shy of municipal elections, and six months away from a presidential election he hopes to contest, he survives. But the political tradition he represents, a synthesis of Islamism and the free market, is hurt, the prime minister has been badly damaged, and there will be more damage to come.

Before the Erdoğan–Gülen confrontation started to show itself, in early 2013, and certainly before last summer’s nationwide protests, when Turkish liberals took to the streets against their authoritarian prime minister, Turkey’s modernizing Islamist current enjoyed much goodwill. Erdoğan personified it. He came to power in 2003, after a decades-long struggle by Islamists against the oppressive tactics of the country’s long-entrenched secular institutions, notably the army and judiciary. Within a few years of becoming prime minister, Erdoğan seemed to be rectifying many of the country’s problems. Exploiting the strong majority enjoyed by the AKP in parliament, he stabilized and liberalized the erratic, semi-planned economy, making Turks richer than they had ever been, and introduced numerous liberal reforms (such as ending torture and giving increased rights to the Kurds). Perhaps most important of all, he brought under control of the elected civil authorities the armed forces, which had overthrown no fewer than four elected governments since 1960.

All along, the AKP was in an unofficial coalition with less visible Islamists, and their most powerful coalition partner was the movement of Fethullah Gülen. His schools turned out well-behaved, patriotic, pious Turks, and the government welcomed them into the bureaucratic and business elites that gradually displaced the old secular guard. Erdoğan and Gülen seemed to embody the longing of many Turks for an Islam in harmony with electoral democracy, entrepreneurship, and consumerism. And the Islamic element in the formula was supposed to guarantee high standards of ethics and behavior. For years, public life had been venal, loutish, and appetite-driven; the Islamists promised to do things differently.

But the Islamists, too, do not lack for appetites. Shortly after the initial detentions by Gülen’s police allies in December, a video purporting to show a senior AKP figure in flagrante delicto was posted on the Internet. (Abdurrahman Dilipak, a leading pro-government columnist, claimed there were forty more such “doctored” tapes in existence.) Recorded phone conversations involving Gülen have also been leaked and heard by millions. In one he is deciding which Turkish firm should receive a contract offered by a foreign government. In another, he and a lieutenant discuss the likelihood that three “friends” (i.e., followers) in senior positions at Turkey’s banking regulatory body will protect a Gülen-affiliated bank, Bank Asya, from government investigation. (Shortly after the leak, the three officials in question lost their jobs.) All this seemed a long way from the image of a frugal sage ailing gently in the hills of Pennsylvania that Gülen has cultivated.

The tone of the conflict is unrestrained, and is being set from the top. Erdoğan refuses to utter Gülen’s name in public, but when he talks of “false prophets, seers, and hollow pseudo-sages,” his target is clear. In one of the frequent sermons that Gülen delivers from his home, reaching big audiences in Turkey by means of supportive television stations and the Internet, the exiled preacher recently placed a malediction on his enemies, beseeching God to “consume their homes with fire, destroy their nests, break their accords.” Allegations of extensive government corruption, many of them involving rigged contracts for construction projects and the violation of zoning laws, have been repeated by the Gülenist media often enough for many of them to stick. On February 24, recordings of telephone conversations between the prime minister and his son, Bilal, in which the two plan the hiding of tens of millions of euros, were posted on YouTube. The prime minister has called the recordings fabricated, but the posting in question was viewed some two million times in the twenty-four hours after it was uploaded. Even if Erdoğan’s purges of the judiciary and the police mean that there will not be successful prosecutions (and Turkey’s parliamentary immunity will protect some of Erdoğan’s allies), it is hard to imagine the government regaining its former reputation for probity.

The terrain of the dispute is as much commercial as political. The government has accused the Gülen-affiliated Bank Asya of buying $2 billion in foreign currency shortly before December’s police operations, the implication being that bank officials had been tipped off and anticipated the ensuing fall of the Turkish lira. The bank is now struggling to contain a run on deposits that saw its share price fall by 46 percent between December 16 and February 5. Even non-Gülenist financial experts believe that the government has orchestrated the withdrawals in an attempt to ruin Bank Asya, heedless of the collateral damage, both to small depositors and the banking system as a whole, that this would cause. Turkish capitalism is only tenuously governed by the rule of law.

Erdoğan’s image is suffering. Last summer’s protests disclosed to the public a prime minister ruled by rage and fear, as he reacted to the dissatisfaction of a largely secular minority not with magnanimous gestures, which would have satisfied many of the protesters, but with baton charges, tear gas, and denunciations of a plot by outside powers, sustained by a sinister “interest rate lobby,” to deny Turkey its rightful place in the sun. By “interest rate lobby” Erdoğan means unscrupulous Western speculators—Jews, by implication—and his remarks speak to older memories, among them of Turkey’s indebtedness to European bankers in Ottoman times, which weakened the empire before its collapse in World War I. But he is also evoking the grim 1990s, when an inflationary, debt-ridden, and unproductive economy was the plaything of investors who took profits when the markets were up and reentered after the inevitable crash—benefiting from real interest rates that averaged 32 percent.

These traumas have informed Erdoğan’s approach to the monetary aspects of the crisis. Even before December 17, a combination of the Federal Reserve’s tapering of bond purchases, the threat of rising global interest rates, evidence that the Turkish economy was cooling, and political jitters caused by last summer’s protests had reduced the value of the lira by 9 percent. The decline accelerated after the December arrests, but the prime minister only endorsed a hike in interest rates after the value of the currency had fallen by a further 13 percent, and Turkish companies, with their heavy exposure to short-term, dollar-denominated debt, were struggling to meet financial obligations. Finally, on January 28, the Central Bank raised rates and the lira’s fall was arrested.

Erdoğan’s ideological resistance to raising rates has cost Turkish companies dearly. In the words of Inan Demir, an economist at Finansbank, in Istanbul:

There was no choice but to hike, or there would have been full-scale panic, but it should have been done earlier. Now Turkish companies have the worst of all worlds, with continuing difficulties in meeting redemptions, due to the weak lira, and higher financing costs because of the rate hike.

In the space of just four months, Finansbank has revised its growth forecast for 2014 from 3.7 percent to 1.7 percent—after a decade of growth averaging more than 5 percent.

For all its troubles, Turkey’s economy is still big, its citizens 43 percent better off than they were when Erdoğan came to power. This more successful country is the subject of The Rise of Turkey: The Twenty-First Century’s First Muslim Power, a new book by Soner Cagaptay, a Turkey expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. One sympathizes with Cagaptay, who finished his book long before the present crisis, but even then his tone might have struck one as triumphal—a reminder of the tendency of many observers, captivated by the spectacle of Turkey shedding the complexes of the past, to downplay the perils of the future. Cagaptay dwells at length on the political and economic advances of the Erdoğan years, but he does not go into the tensions within Turkish Islamism, which are likely to define the country’s politics for some time, or the corruption that underlies the country’s capitalist successes.

The Rise of Turkey is also quiet about the Gülen movement—except for its part in organizing a glittering international conference, attended by Cagaptay, on Turkey’s “leadership role in the Arab Spring.” Such a conference would be unthinkable now, for Erdoğan’s Muslim Brotherhood allies have been bundled out of power in Egypt and his Syrian policy, predicated on a swift overthrow of Bashar al-Assad, is in disarray. Cagaptay is far from the only academic to have accepted hospitality from the Gülen movement, and his description of it as “prestigious” cannot be contested. But there is more to Fethullah Gülen than prestige.