A Ramshackle Modernity

‘The Time Regulation Institute,’ by Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar

By MARTIN RIKER

We’re having a particularly good season for literary discoveries from the past, with recent publications of Volumes 1 and 2 of Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq’s “Leg Over Leg” (1855), the marathon translation of Giacomo Leopardi’s 2,600-page “Zibaldone” (1898) and now “The Time Regulation Institute” (1962), the second great novel from Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar. They arrive, such books, in a category all their own, in one sense new, in another sense old, as if to remind us that this thing called literature is much larger than our own little moment.

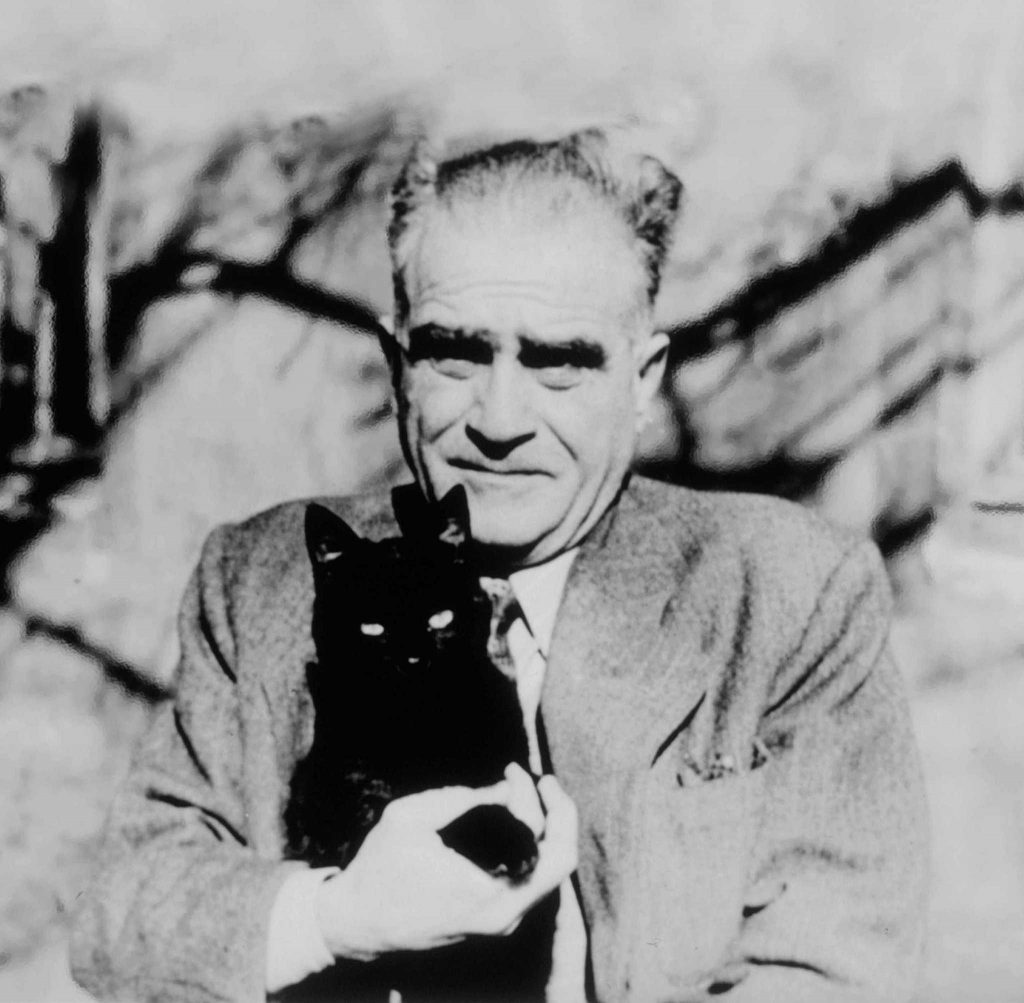

Tanpinar (1901-62) was a formative figure in modern Turkish letters, although 50 years after his death, his career in English is just getting off the ground. His monumental “A Mind at Peace” (1949), which Orhan Pamuk has called “the greatest novel ever written about Istanbul,” found its way into English in 2008. Set just before World War II, it conjures on a vast scale the world of Istanbul during the early Turkish Republic, a time when modern Western values were abruptly imposed upon a people and a culture unprepared for them. The ramshackle modernity that resulted, in which Ottoman history and tradition were largely written over, became Tanpinar’s lasting subject: the “void,” as he once described it, of a people “suspended between two lives.”

Years later, Tanpinar revisited this void, but more overtly and comically, in his other major novel, “The Time Regulation Institute.” Having floated around for some years in a little-known English edition from a Turkish publisher, this excellent book has now landed more firmly in a new translation by Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe, published by Penguin Classics. The Penguin edition provides plenty of context, including a timeline of Turkish history, an explanatory note from the translators, text notes, and an introduction by Pankaj Mishra detailing the cultural history behind Tanpinar’s work. Yet with so much packaging, it also suffers a little from that tic we sometimes bring to translated literature, of making the foreign book seem more foreign than it is.

For all its historical and cultural specificity, “The Time Regulation Institute” is before all else a first-rate comic novel, one with a fairly large foot in the Western literary tradition called Menippean satire. Works within the orbit of this genre stretch across the centuries, including Aristophanes’ “The Clouds,” Erasmus’s “In Praise of Folly,” Huxley’s “Point Counter Point” and those “Fortuna’s wheel” sections of Toole’s “A Confederacy of Dunces.” What such otherwise dissimilar books have in common is a delight in exposing the limits of human reason, with particular scorn for any intellectual system that attempts to comprehensively explain the world. Throughout history, whenever a theory arises that seeks to encapsulate human experience — politically, philosophically, economically, whatever — a Menippean satire emerges to make fun of it. So too with “The Time Regulation Institute,” in which Tanpinar creates an allegorical premise at once specific and broad enough to effectively satirize the entire 20th century, a century of systems if ever there was.

The book presents itself as the memoir of Hayri Irdal, assistant head manager of the ill-fated Time Regulation Institute and author of the once famous, now infamous (because entirely fake) historical study “The Life and Works of Ahmet the Timely.” Irdal is an earnest if slippery old fellow, who constantly professes his ignorance even while pointing out his accomplishments, and who regularly digresses into side notes that tend to be rather smart. “Sometimes I consider just what strange creatures we are,” he says; “we bemoan the brevity of our lives but do everything in our power to squander this thing we call ‘the day’ as quickly and mindlessly as we can.” The sudden death of his longtime mentor, the entrepreneur Halit Ayarci, has provided Irdal with the opportunity to reflect upon the incredible course his life has taken — a course that resembles at many turns the journey of the Turkish people into modernity — and he now wishes to set the record straight on a number of key points.

What follows is the story of a life unusually indebted to timepieces. First is the grandfather clock that stood at the center of several generations of Irdal’s family history. Next we learn about the loss of personal freedom he experienced around age 10, upon receiving a watch from his uncle. “First the little timepiece nullified my little world,” Irdal tells us, “and then it claimed its rightful place, forcing me to abandon my earlier loves.” But the real turn comes with his apprenticeship to the wise old clock repairman, Nuri Efendi. It is from Nuri that Irdal picks up the various sage one-liners — “Regulation is chasing down the seconds!” — that will eventually catch the attention of Halit Ayarci, on the very first occasion they meet. “Think about the implications of these words,” Ayarci tells Irdal. “We’re losing half our time with unregulated clocks. If every person loses one second per hour, we lose a total of 18 million seconds in that hour. . . . Now perform the calculations and see how many lifetimes suddenly slip away every year. . . . Can you now see the immensity of Nuri Efendi’s mind, his genius? Thanks to his inspiration, we shall make up the loss.” Thus will the Time Regulation Institute eventually be born: from a handful of one-liners transformed into slogans, attributed to a historically fabricated “Ahmet the Timely,” and plastered on posters throughout the land.

I won’t say more here about the elaborate allegory Tanpinar builds around his “Institute” (almost everything I’ve described so far is found in the first 30 pages), except that it ends up being the most comprehensive satire of what we would call NGOs and nonprofit organizations I’ve ever read. Nor are regulation and bureaucracy Tanpinar’s only targets, for each character he introduces along the way brings into the book another lofty belief system ready to be lampooned. Alchemy, spiritualism, psychoanalysis, politics, academic theorizing, Hollywood romanticism — at times Tanpinar’s novel reads like an encyclopedia of human folly. And when the Time Regulation Institute is finally founded (more than halfway through the book), it seems no coincidence that the passengers on this ship of fools all sign on as its first employees.

Tanpinar’s comedy is driven more by characters than language. There are not many belly laughs, or even jokes, but rather absurd situations in which hypocrisies are laid plain. At times the story gets baggy with secondary characters and their domestic plots of love and disillusionment, and despite a very lively translation, the Turkish names and honorifics can be difficult to keep straight. In the end, however, none of this gets in the way of the book’s ability to be not only entertaining and substantial but also, for lack of a better word, timely. For beyond the historical relevance, beyond the comic esprit, Tanpinar’s elaborate bittersweet sendup of Turkish culture over a half-century ago speaks perfectly clearly to our own, offering long-distance commiseration to anyone whose life is twisted around schedules and deadlines — pretty much everyone, in other words — provided you can find the time to read it.

THE TIME REGULATION INSTITUTE

By Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar

Translated by Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe

401 pp. Penguin. Paper, $18.