By TIMUR KURAN

Times Topic: Middle East Protests (2010-11)

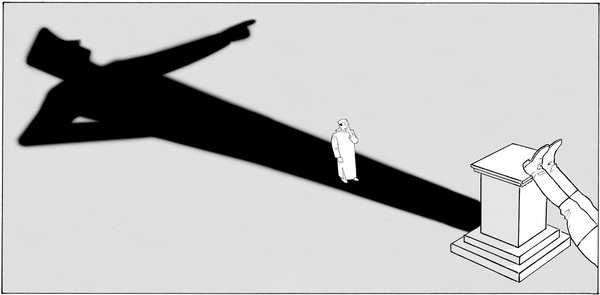

THE protesters who have toppled or endangered Arab dictators are demanding more freedoms, fair elections and a crackdown on corruption. But they have not promoted a distinct ideology, let alone a coherent one. This is because private organizations have played only a peripheral role and the demonstrations have lacked leaders of stature.

Both limitations are due to the longstanding dearth, across the Arab world, of autonomous nongovernmental associations serving as intermediaries between the individual and the state. This chronic weakness of civil society suggests that viable Arab democracies — or leaders who could govern them — will not emerge anytime soon. The more likely immediate outcome of the current turmoil is a new set of dictators or single-party regimes.

Democracy requires checks and balances, and it is largely through civil society that citizens protect their rights as individuals, force policy makers to accommodate their interests, and limit abuses of state authority. Civil society also promotes a culture of bargaining and gives future leaders the skills to articulate ideas, form coalitions and govern.

The preconditions for democracy are lacking in the Arab world partly because Hosni Mubarak and other Arab dictators spent the past half-century emasculating the news media, suppressing intellectual inquiry, restricting artistic expression, banning political parties, and co-opting regional, ethnic and religious organizations to silence dissenting voices.

But the handicaps of Arab civil society also have historical causes that transcend the policies of modern rulers. Until the establishment of colonial regimes in the late 19th century, Arab societies were ruled under Shariah law, which essentially precludes autonomous and self-governing private organizations. Thus, while Western Europe was making its tortuous transition from arbitrary rule by monarchs to democratic rule of law, the Middle East retained authoritarian political structures. Such a political environment prevented democratic institutions from taking root and ultimately facilitated the rise of modern Arab dictatorships.

Strikingly, Shariah lacks the concept of the corporation, a perpetual and self-governing organization that can be used either for profit-making purposes or to provide social services. Islam’s alternative to the nonprofit corporation was the waqf, a trust established in accordance with Shariah to deliver specified services forever, through trustees bound by essentially fixed instructions. Until modern times, schools, charities and places of worship, all organized as corporations in Western Europe, were set up as waqfs in the Middle East.

A corporation can adjust to changing conditions and participate in politics. A waqf can do neither. Thus, in premodern Europe, politically vocal churches, universities, professional associations and municipalities provided counterweights to monarchs. In the Middle East, apolitical waqfs did not foster social movements or ideologies.

Starting in the mid-19th century, the Middle East imported the concept of the corporation from Europe. In stages, self-governing Arab municipalities, professional associations, cultural groups and charities assumed the social functions of waqfs. Still, Arab civil society remains shallow by world standards.

A telling indication is that in their interactions with private or public organizations, citizens of Arab states are more likely than those in advanced democracies to rely on personal relationships with employees or representatives. This pattern is reflected in corruption statistics of Transparency International, which show that in Arab countries relationships with government agencies are much more likely to be viewed as personal business deals. A historically rooted preference for personal interactions limits the significance of organizations, which helps to explain why nongovernmental organizations have played only muted roles in the Arab uprisings.

Timur Kuran, a professor of economics and political science at Duke, is the author of “The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held Back the Middle East.”

Read More : The Weak Foundations of Arab Democracy – NYTimes.com.

Leave a Reply