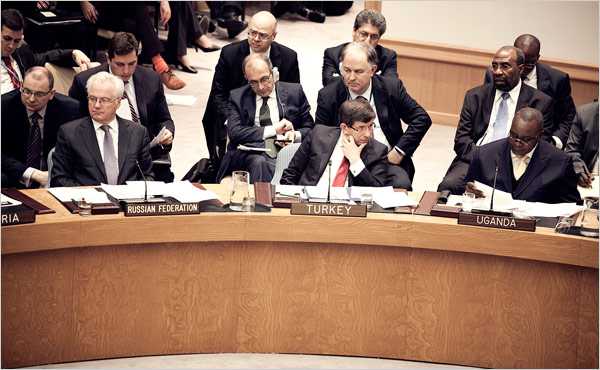

PLAYING PEACEMAKER Turkey’s Ahmet Davutoglu during a United Nations Security Council meeting in December, discussing the future of Iraq.

By JAMES TRAUB

Published: January 20, 201

In the fall of 2009, relations between Serbia and Bosnia — never easy since the savage civil war of the 1990s — were slipping toward outright hostility. Western mediation efforts had failed. Ahmet Davutoglu, the foreign minister of Turkey, offered to step in. It was a complicated role for Turkey, not least because Bosnia is, like Turkey, a predominantly Muslim country and Serbia is an Orthodox Christian nation with which Turkey had long been at odds. But Davutoglu had shaped Turkey’s ambitious foreign policy according to a principle he called “zero problems toward neighbors.” Neither Serbia nor Bosnia actually shares a border with Turkey. Davutoglu, however, defined his neighborhood expansively, as the vast space of former Ottoman dominion. “In six months,” Davutoglu told me in one of a series of conversations this past fall, “I visited Belgrade five times, Sarajevo maybe seven times.” He helped negotiate names of acceptable diplomats and the language of a Serbian apology for the atrocities in Srebrenica. Bosnia agreed, finally, to name an ambassador to Serbia. To seal the deal, as Davutoglu tells the tale, he met late one night at the Sarajevo airport with the Bosnian leader Haris Silajdzic. The Bosnian smoked furiously. Davutoglu, a pious Muslim, doesn’t smoke — but he made an exception: “I smoked; he smoked.” Silajdzic accepted the Serbian apology. Crisis averted. Davutoglu calls this diplomatic style “smoking like a Bosnian.”

Peter Yang for The New York Times

Davutoglu (pronounced dah-woot-OH-loo) has many stories like this, involving Iraq, Syria, Israel, Lebanon and Kyrgyzstan — and most of them appear to be true. (A State Department official confirmed the outlines of the Balkan narrative.) He is an extraordinary figure: brilliant, indefatigable, self-aggrandizing, always the hero of his own narratives. In the recent batch of State Department cables disclosed by WikiLeaks, one scholar was quoted as anointing the foreign minister “Turkey’s Kissinger,” while in 2004 a secondhand source was quoted as calling him “exceptionally dangerous.” But his abilities, and his worldview, matter because of the country whose diplomacy he drives: an Islamic democracy, a developing nation with a booming economy, a member of NATO with one foot in Europe and the other in Asia. Turkey’s prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is a canny, forward-thinking populist who has drastically altered Turkish politics. Erdogan and Davutoglu share a grand vision: a renascent Turkey, expanding to fill a bygone Ottoman imperial space.

In a world that the U.S. no longer dominates as it once did, President Barack Obama has sought to forge strong relations with rising powers like India and Brazil. Turkey, however, is the one rising power that is located in the danger zone of the Middle East; it’s no coincidence that Obama chose to include Turkey in his first overseas trip and spoke glowingly of the “model partnership” between the two countries. This fits perfectly with Turkey’s ambition to be a global as well as a regional player.

And yet, despite all the mutual interests, and all of Davutoglu’s energy and innovation, something has gone very wrong over the last year. The Turks, led by Davutoglu, have embarked on diplomatic ventures with Israel and Iran, America’s foremost ally and its greatest adversary in the region, that have left officials and political leaders in Washington fuming. Obama administration officials are no longer sure whose side Turkey is on.

Davutoglu views the idea of “taking sides” as a Cold War relic. “We are not turning our face to East or West,” he told me. But it is almost impossible to have zero problems with neighbors if you live in Turkey’s neighborhood.

Istanbul is full of elegant and cosmopolitan intellectuals, few of whom had heard of Ahmet Davutoglu when he was named foreign-policy adviser to the prime minister in 2002. “Outside of Islamic circles,” says Cengiz Candar, a columnist for the daily Radikal, “he was not much known at all.” The victory of the moderate Islamist AK party in the 2002 parliamentary elections was a seismic event in Turkey, culturally as well as politically. Turkey had been an aggressively secular republic since its establishment in 1923; Turkey’s Westernized intellectuals, living in the coastal cities, especially Istanbul, looked upon the Islamists as bumpkins from the Anatolian hinterland. “These people came out of nowhere,” as Candar puts it.

Davutoglu, who is 51, hails from Konya, on the Anatolian plateau; though his English is excellent, he often drops definite articles, a sign that he came to the language relatively late. He has a slight mustache from under which a gentle and bemused smile usually pokes out. He is religiously observant; his wife, a doctor, wears a head scarf. Yet he has become surprisingly popular even among Turkey’s secular elite. “Deep in the Turkish psyche,” Candar says, “there is a feeling of pride and grandeur.” Turkey is not just another country, after all, but the heir of empires, classical as well as Ottoman, and the first secular republic in the Islamic world. Both in his intellectual work, which argues for the extraordinary status Turkey enjoys by virtue of its history and geographical position, and in his role as foreign minister, Davutoglu is seen as a champion of Turkish greatness.

He was an academic before he was a diplomat. His book “Strategic Depth,” published in Turkish in 2001, is regarded as the seminal application of international-relations theory to Turkey, though it is also a work of civilizational history and philosophy. (Such is Davutoglu’s intellectual ambition that he planned to follow up with “Philosophical Depth,” “Cultural Depth” and “Historical Depth.” He hasn’t yet gotten around to the others.) The book has gone through 41 printings in Turkish and has been translated into Greek, Albanian and now Arabic. It is 600 pages long, very dense and almost certainly more known than read. One of Davutoglu’s aides describes the book as “mesmerizing.” (Henri Barkey, a Turkey scholar at Lehigh University, pronounces the work “mumbo jumbo,” adding that Davutoglu “thinks of himself as God.”) “Strategic Depth” weaves elaborate connections between Turkey’s past and present, and among its relations in the Middle East, the Caucasus, the Balkans and elsewhere. The book was read as a call for Turkey to seize its destiny.

And in many ways, Turkey has. It is one of the great success stories of the world’s emerging powers. Shrugging off the effects of the global recession, the Turkish economy last year grew by more than 8 percent, and Turkey has become the world’s 17th-largest economy. Turkey is the “soft power” giant of the Middle East, exporting pop culture and serious ideas and attracting visitors, including one and a half million Iranians a year, to gape at the Turkish miracle. Paul Salem, a Lebanon-based Middle East scholar with the Carnegie Endowment, recently suggested, “It might be Turkey’s century, because it’s the only country in the Middle East actually pointing toward the future.” You increasingly hear the view that power in the Middle East is shifting away from Arab states and toward the two non-Arab powers, Turkey and Iran. Indeed, in “Reset: Iran, Turkey and America’s Future,” Stephen Kinzer, a former New York Times reporter, describes Turkey, Iran and the U.S. as “the tantalizing ‘power triangle’ of the 21st century,” destined to replace the Cold War triangle of the U.S., Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Davutoglu has climbed aboard the Turkish rocket. Turkey’s success raises his status; his achievements do the same for his country. Foreign Policy magazine ranked him No. 7 in its recent list of “100 Global Thinkers,” writing that under his leadership, “Turkey has assumed an international role not matched since a sultan sat in Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace.” Davutoglu has maintained close relations with both Erdogan and President Abdullah Gul — one of the few senior figures to do so. He has filled the upper ranks of the foreign-affairs ministry with worldly, pragmatic, thoughtful diplomats who share his nationalist vision. They have done an extraordinarily deft job of balancing Turkey’s regional and global ambitions, of advancing its interests without setting off alarm bells in other capitals.

Sometimes, it’s true, Davutoglu sees his role as more important than it actually is. He told me a wonderful anecdote about bringing Iraq’s Sunni factions together in Baghdad in the fall of 2005, letting them yell at one another for weeks and finally shaming them into joining together by reminding them of the glories of medieval Baghdad and, by implication, of Iraq itself. In this version, a thrilled Zalmay Khalilzad, the American ambassador to Iraq, rushes to Istanbul to bless the union. Actually, says a former U.S. official very familiar with the event, it wasn’t a breakthrough at all. In fact, the official says, when President Gul called Khalilzad to implore him to come, the American diplomat asked, “Why do we need to go all the way to Istanbul to talk to the same people we talk to all the time?” However, “as a favor to Gul, he said, ‘Sure.’ ”

In Davutoglu’s own endlessly unwinding narratives, he is always speaking like a Baghdadi and smoking like a Bosnian and untying all Gordian knots. Every once in a while during our conversations, Davutoglu would raise a finger and say, “This you can quote.” This meant that he was about to say something really dazzling. On the other hand, he is pretty dazzling, leaping nimbly from Mesopotamia to Alexander the Great to the Ottoman viziers to today’s consumerism, drawing unlikely parallels and surprising lessons.

Davutoglu began his career as foreign-policy adviser at a moment when Turkey’s bid for membership in the European Union had become a national obsession. For Davutoglu, Erdogan and Gul, being in the E.U. offered Turkey crucial economic benefits but, more important, confirmation of its belonging in the club of the West. The Erdogan government pursued difficult economic and political reforms to advance its candidacy, then fumed as less-qualified but predominantly Christian countries like Cyprus — represented by the government of Greek Cyprus, an avowed foe of Ankara — zoomed past to full membership. Major European countries, above all France and Germany, seem determined to block Turkey’s accession to the E.U. This past June, Defense Secretary Robert Gates even suggested that “if there is anything to the notion that Turkey is, if you will, moving Eastward,” it was the result of having been “pushed by some in Europe refusing to give Turkey the sort of organic link to the West that Turkey sought.”

This is a very common refrain, which Davutoglu is at pains to refute. On a flight to Ankara from Brussels, where he had just attended a NATO meeting, Davutoglu pushed away his half-eaten dinner and recited to me what he told his fellow foreign ministers: “If today there is an E.U., that emerged under the security umbrella of NATO. And who contributed most during those Cold War years? Turkey. Therefore when someone says, ‘Who lost Turkey?’ — there was such a question, because people said Turkey was turning to the East — this is an insult to Turkey. Why? Because it means he does not see Turkey as part of ‘we.’ It means Turkey is object, not subject. We don’t want to be on the agenda of international community as one item of crisis. We want to be in the international community to solve the crisis.”

To be part of the global “we” — this was the very definition of Erdogan’s, and Davutoglu’s, ambitions. This is why the Turks received the European rebuff as such a deep insult. And it is true, as Gates suggested, that in the aftermath, Turkey sought to raise its status in the immediate neighborhood. One of Davutoglu’s greatest diplomatic achievements was the creation of a visa-free zone linking Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria, thus reconstituting part of the old Ottoman space. The four countries have agreed to move toward free trade, as well as free passage, among themselves. As part of the zero-problems policy, Turkey moved to resolve longstanding tensions with Cyprus and Armenia and, more successfully, with Greece and Syria. Turkey’s decades of suppression of Kurdish demands for autonomy put it at odds with the new government of Iraqi Kurdistan, which sheltered Kurdish resistance fighters. But the Erdogan government reached out to Kurdistan, America’s strongest ally in the region. Relations with the Bush administration had been rocky since 2003, when Turkey’s Parliament voted against permitting U.S. forces to enter Iraq through southeastern Turkey. But by now the U.S. was eager to use Turkey as a force for regional stability. The rapprochement with Kurdistan thus smoothed relations with Washington and made Turkey a major player in Iraqi affairs. Turkish firms gained a dominant position not only in Kurdistan but also, increasingly, throughout Iraq. And Iraqi Kurdish leaders had cracked down on the rebels. It was a diplomatic trifecta.

But Davutoglu’s vision extended far beyond securing the neighborhood for Turkish commerce. One of his pet theories is that the United States needs Turkey as a sensitive instrument in remote places. “The United States,” he says, in his declamatory way, “is the only global power in the history of humanity which emerged far away from the mainland of humanity,” which Davutoglu calls Afro-Eurasia. The United States has the advantage of security and the disadvantage of “discontinuity,” in regard to geography as well as history, because America has no deep historic relationship to the Middle East or Asia. In Davutoglu’s terms, the U.S. has no strategic depth; Turkey has much. “A global power like this, a regional power like that have an excellent partnership,” Davutoglu concludes with a flourish. Turkey has used its web of relations, especially in the Sunni world, to advance American interests in Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan, where Turkey recently agreed to renew its NATO mandate as the commander of the troop contingent in Kabul.

In 2007, Turkey put itself forward as a Middle East peacemaker. Ottoman Turkey was a safe harbor for Jews when much of Europe was aflame with anti-Semitism. And Republican, secular Turkey was Israel’s most dependable ally in the Middle East. Many Turkish Islamists despise Israel, but Erdogan and the AK adopted a more diplomatic line. Erdogan visited Israel in 2004, and in 2007 Turkey invited Israel’s president, Shimon Peres, to address Parliament — a rare honor. Turkish leaders then sought to broker talks between Syria and Israel over the return of the Golan Heights to Syria. At the time, the Bush administration had cut off relations with Syria, which it viewed as a proxy for Iran; but Israel was eager for an interlocutor with Damascus. The role of go-between “was not assigned to Turkey by any outside actor,” Davutoglu wrote in an essay in Foreign Policy. Turkey assigned the task to itself under a principle he called “proactive and pre-emptive peace diplomacy.” This is what it means to be part of “we.”

Davutoglu says he shuttled between the capitals 20 times in 2007, and in 2008 he brought both sides to Istanbul for five rounds of talks in separate hotels. He carried messages back and forth between the two. Israel needed to be convinced that Syria was prepared to stop sponsoring Hezbollah and to distance itself from Iran. Syria demanded that Israel clarify the territory from which it was prepared to withdraw. By late December, Davutoglu and his aides say, only disagreement over a word or two prevented the two sides from moving to direct talks. Prime Minister Ehud Olmert of Israel held a five-hour dinner at Erdogan’s home, in the course of which both men spoke to President Bashar al-Assad of Syria. Davutoglu had reserved a hotel room for the direct talks. An Israeli official close to the negotiations confirmed this account, saying that Davutoglu “played a very important role, a very professional role” and agreeing that face-to-face talks seemed to be in the offing. Olmert himself was quoted earlier this year as calling Erdogan “a fair mediator” and as saying, “We need negotiations with Turkish mediation.”

But it was all what might have been, for only a few days after the meeting, Israel launched its Cast Lead invasion of Gaza, inflaming the Arab world and humiliating and infuriating Erdogan. The talks collapsed. The Israeli official says, “We told the Turks that we will have to respond” to the hail of missiles coming from Gaza; Israel had not deceived the Turks, because Israel’s cabinet authorized the invasion days after the Olmert-Erdogan dinner. That’s not how Turkey saw the sequence of events. It was, Davutoglu says solemnly, “an insult to Turkey.” Certainly the Turkish public felt it as one, and Erdogan, a shrewd judge of public opinion, understood that very well. Turkey is a democracy, after all; and the public reaction to Gaza, on top of the rebuff from the European Union — and perhaps also the inherent logic of the “zero problems” policy — sent the country in a new direction.

Turkey’s interests in the Balkans, in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, and for that matter in Israel, coincided with those of the United States and the West. But its run of luck ended in Iran. In September 2009, the Iranians, under pressure from the West to show that they were not seeking to build a nuclear weapon, offered to send 1,200 kilograms of uranium abroad in exchange for an equal amount to be enriched sufficiently for civilian use. Iran didn’t trust any Western country to hold its uranium; but it might trust Turkey. Davutoglu sprang into action, flying back and forth to Tehran to work out the details — over which the Iranians, typically, bickered and stalled.

The cables recently disclosed by WikiLeaks vividly illustrate the tensions this produced with Washington. In a meeting with the assistant secretary of state Philip Gordon in Ankara in November 2009, Davutoglu advanced his theory of Turkish exceptionalism: “Only Turkey,” he said, “can speak bluntly and critically to the Iranians.” Davutoglu was confident that Iran was ready to strike a deal — with Turkey’s help. An obviously skeptical Gordon “pressed” him on his “assessment of the consequences if Iran gets a nuclear weapon.” In what the cable’s author described as “a spirited reply,” Davutoglu insisted that Turkey was well aware of the risk. Gordon “pushed back that Ankara should give a stern public message” to Iran; Davutoglu replied that they were doing so in private and “emphasized that Turkey’s foreign policy is giving ‘a sense of justice’ and ‘a sense of vision’ to the region.”

Behind this tense exchange with Gordon was the fear that Turkey was cutting Iran too much slack. Davutoglu is quite open about the fact that Turkey has interests in Iran that the United States and Europe do not have. “Our economy is growing,” Davutoglu told me, “and Iran is the only land corridor for us to reach Asia. Iran is the second source of energy for Turkey.” Sanctions on Iran would hurt Turkey. But Davutoglu also insists that Turkey’s assessment of Iran’s intentions is not affected by its interests. It’s easy to see why Gordon was skeptical. Prime Minister Erdogan has dismissed fears that Iran wants to build a bomb as “gossip.” And when I asked one of Davutoglu’s senior aides about the matter, he said: “For the time being, Iran does not have a nuclear-weapons program. We don’t know whether they will go there.”

At President Obama’s nuclear summit meeting last April, Erdogan and the president of Brazil, Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, proposed to Obama that they work jointly to persuade Iran to surrender the uranium — a striking example of the rising confidence of the emerging powers. Administration officials made it very clear that they feared Iran would try to hoodwink Turkey and Brazil. Davutoglu nonetheless resumed his manic routine — State Department officials call him the Energizer Bunny — flying back and forth to Tehran well into May, pushing the Iranians to make concessions. In his seventh and final session, he worked at it for 18 hours before reaching a deal. Davutoglu was so excited that he called Turkish reporters from the plane to invite them to a briefing upon his arrival. But by the time the journalists returned to their offices to write the story, they got word that the United States had rejected the deal.

The Turks had announced their diplomatic coup at precisely the moment the Obama administration finally induced Russia and China to vote for tough sanctions on Iran in the Security Council. Davutoglu says he never took a step without informing the Americans, but American officials said that the terms of the deal took them by surprise. The Turks mostly hid their hurt feelings. But in early June, the rift with the U.S. played out in public when Turkey and Brazil voted against the sanctions resolution. Turkish officials say the last thing they wanted was to defy the U.S. on a matter of American national security, but President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran said he would consider the “swap deal” terminated unless Turkey and Brazil voted against the resolution. They were, they insist, voting for continued diplomacy, not for Iran or against the United States and the West.

Maybe Turkey was simply protecting its regional interests, which now include not only preserving good relations with Iran but also enhancing its credibility in the Middle East — even at the expense of its standing in the West. Maybe, for all Davutoglu’s protestations, Ankara doesn’t view the world the way Washington does or London does. In a meeting earlier this year at the Council on Foreign Relations, Henri Barkey observed that when you talk to Erdogan or Davutoglu about Iran, “the response is almost as if you pressed a button: the problem is not Iran; the problem is Israel; Israel has weapons; Iran doesn’t have weapons.” Or maybe the problem is that you can’t have zero problems with everybody.

Iran, unfortunately, was only the half of it. The other half was Israel. Three weeks after the Gaza war, Erdogan angrily stalked out of a public session with Shimon Peres at Davos, Switzerland. Israel responded with equal pettiness, staging a humiliation of Turkey’s ambassador to Israel. Erdogan, long a champion of Hamas, became more vocal in his support for a group Israel viewed as a threat to its very existence. In the spring of 2010, a Turkish charitable organization, I.H.H., chartered the flotilla designed to break Israel’s blockade of Gaza. Davutoglu says that he tried to persuade the group not to sail and then asked the organizer of the flotilla to turn aside if Israel stopped the ships, as it was certain to do, and to offload the cargo at a port outside Gaza if necessary. In late May, the day before the flotilla set sail, a senior Turkish official called the Israelis to alert them to the ships’ embarking and to say, “Please don’t engage in violence.”

Of course, it didn’t work out that way. The flotilla refused Israel’s demands to alter course, and a helicopter-borne commando assault on the Mavi Marmara, the lead ship, turned deadly, with eight Turkish citizens and one American killed. The Gaza war had embittered Turkish public opinion; now angry crowds gathered across the country, denouncing Israel and chanting Islamic slogans. Erdogan railed against Israel and stoutly defended Hamas, denying that it was a terrorist organization. He described Israel, with which he had been earnestly negotiating a year earlier, as “a festering boil in the Middle East that spreads hate and enmity.” Turkey demanded an apology. Israel, which viewed the flotilla as a provocation abetted, and perhaps orchestrated, by Ankara, refused. Davutoglu was almost as inflammatory as his prime minister. In a statement to the Security Council the day after the assault, he said, “This is a black day in the history of humanity, where the distance between terrorists and states has been blurred.”

Turkey seemed to have made a choice among its conflicting ambitions. Steven Cook, a Middle East scholar at the Council on Foreign Relations, recently wrote, “Erdogan and his party believe they benefit domestically from the position Turkey has staked out in the Middle East,” and thus “the demands of domestic Turkish politics now trump the need to maintain good relations with the United States.” Turkey may be turning in a new direction, in other words, not so much because it has been rejected by the West as because it is being so ardently embraced by the East.

The net effect of Turkey’s vehement reaction to the flotilla, which by an unfortunate quirk of timing came two weeks after the nuclear deal with Iran and a week before the sanctions vote, was to wreck whatever remained of its relations with Israel and to seriously harm its standing in the U.S. “The hyperbolic and provocative rhetoric” in the aftermath of the Mavi Marmara incident, says a senior administration official, “has interfered with what has been a historic and hugely important, positive Turkish-Israeli relationship.” And it has done real damage in the court of public opinion, where Turkey looks like the enemy of the United States’ best friend in the Middle East as well as the friend of its worst enemy. After the Mavi Marmara incident, Thomas L. Friedman asserted in The Times, perhaps hyperbolically, that Turkey had joined “the Hamas-Hezbollah-Iran resistance front against Israel.”

Tempers have cooled in recent months. U.S. officials have tried to encourage a rapprochement between Turkey and Israel. Last June, Israel’s trade minister, Benyamin Ben-Eliezer, invited Davutoglu to speak with him quietly in Brussels. But the contents of the conversation were leaked almost immediately in Israel, presumably by hardliners opposed to any easing of tensions. Relations with Washington remain fraught. “There’s so much we want to do together,” as the official cited above puts it, “but it’s harder for us to do that if the American and Congressional perspective on Turkey is a negative one” — which right now, he added, it is.

A few months before he became Turkey’s foreign minister, Davutoglu visited Washington to meet with the incoming Obama team. He was dazzled. George W. Bush, he thought, had been America’s Caesar; Obama would be its Marcus Aurelius, its philosopher-king. “There will be a golden age in Turkish-American relations,” he predicted. It hasn’t worked out that way, and Davutoglu can barely process a setback so at odds with his grand intellectual and policy construct. He says that he was “shocked” when the U.S. opposed a United Nations Human Rights Council resolution calling for an investigation of “the outrageous attack by the Israeli forces against the humanitarian flotilla.” (The administration said such a commission seemed to be rushing to judgment, and it endorsed instead a panel convened by the U.N. secretary-general.) But the professionals Davutoglu has surrounded himself with are not deluding themselves about their plight. “We’re getting a lot of flak from the Hill,” says Selim Yenel, the official in the foreign ministry responsible for relations with Washington. “We used to get hit by the Greek lobby and the Armenian lobby, but we were protected by the Jewish lobby. Now the Jewish lobby is coming after us as well.”

The truth is that for all his profound knowledge of the history of civilizations, Davutoglu misread the depth of feeling in the U.S. about both Israel and Iran, or perhaps overestimated Turkey’s importance. This is the danger of postimperial grandiosity. “They talk as if they expect a merger between Turkey and the E.U.,” says Hugh Pope, head of the Turkish office of the International Crisis Group. “They think they’re more important than Israel.”

Perhaps the setback is just a blip, a brief reversal in the upward path of one of the world’s rising powers. On the flight home from Brussels, where he conferred privately with Robert Gates and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and met with his European counterparts, Davutoglu was in an ebullient mood. He feels the wind of history filling his sails. Turkey, the crossroads of civilizations, the land where East and West, North and South, converge, is pointing the way to the world’s future. “Turkey is the litmus test of globalization,” he told me. “Success for Turkey will mean the success of globalization.” The world, as Davutoglu likes to say, expects great things from Turkey.

Leave a Reply