BY KATJA HEISE @Translation: Anneka @

Since the start of my politics degree in 2004 at the Philipps University of Marburg, I knew that after a few years I would be going abroad for a semester as an erasmus university exchange student. However, it wouldn’t be to the traditional destinations likeSpain, England or Holland. I wanted to go a bit further away, somewhere a bit more exotic. In the list of universities which Marburg has an exchange agreement with I spotted the USA, Canada and even South Africa. Right at the bottom of the list nestled Istanbul. I knew it straightaway – that’s where I wanted to go.

Living alone in a big city

As my plane begins to descend above Istanbul at Atatürk airport, I get briefly scared. As quick as lightning, everything that could go wrong entered my head. After all, this is my first time in Turkey and I don’t speak a word of Turkish. ‘Everyone speaks English there anyway,’ my erasmus coordinator had promised me. Far from it! Arriving in the girls’ dorm, I am welcomed by three smiling, friendly ladies who give me a strong Turkish coffee to drink, but no-one speaks a word of English. As no other solution comes to mind, I sign a list of dorm rules without understanding its content. That’ll probably turn out okay, I think to myself, until later a student from Estonia explains that I signed a document agreeing to an 8pm curfew, accepting that no visitors are allowed and especially male visits are strictly banned. What’s more, I live with five other girls in one room, and unfortunately no-one speaks English here either. It’s bed to bed on an area measuring 20 square metres. The possession and consumption of alcohol and cigarettes are strictly punished. That isn’t what most young European exchange students expect from their erasmus semester. But erasmus stands for a bit of studying in another country and a great deal of partying, partying and partying.

Bei meiner Ankunft bekomme ich kurz Angst… ich spreche kein Wort Türkisch | ©Objektivist/flickr

Unlike in Germany, the young people have a very intense relationship with their elders, even throughout their twenties. Parents are informed if a student would like to go out or stay out the night. There are also mentors. ‘Ablas’ are older boys and ‘abi’ are older girls who the younger students can talk to, but they also watch out a little that their protégés apply themselves primarily to uni. This system in German dorms would be absolutely unthinkable. Whether that’s a good thing or not is open to debate. I’ve led more than a heated discussion about whether and when young people should be sent out ‘alone’ into life – it’s common when you start your degree in Germany. However, I haven’t witnessed lonely, insecure and often completely overwhelmed young people in Istanbul. Being alone in a big city and not coping without familiar surroundings nor fitting in after a while is sadly more common in Germany.

Political discussions

I’m spending my exchange semester at Fatih University, a conservative private university far from the city centre. In Marburg the lecturers take their time and are available at any moment for one-on-one talks. However at Fatih friendships with the professors develop quickly; you drink coffee together and are on first-name terms with each other. That gives lots of scope for discussions, about politics for example, which are a great deal more controversial than what you’re used to at home.Why democracy? Military dictatorship can govern the state affairs a lot better, argues one politics lecturer at Istanbul university. My initial reaction is speechlessness, then rage as I end up trying to convince by arguing – sometimes with mostly a little success.

Read our series of erasmus accounts of Istanbul from Yeditepe and Halic universities

I learn how to explain my arguments and points of view from their foundations: ‘Why should a popular sovereignty be so good, then?’ In Istanbul I’m learning to challenge my own view of life and not to see words like ‘democracy’ and ‘human rights’ as a universal goal. ‘The military in Turkey has always catered for peace and stability,’ my lecturer argues. ‘If a civil war threatens a country, these aims are the first priority.’ It occurs to me that my ideas of right and wrong are meant for my own little world, to an alarmingly high degree at that. There’s not only one solution. Truths are always just results of initial situations and therefore can’t apply either absolutely or universally. It’s a shame actually.

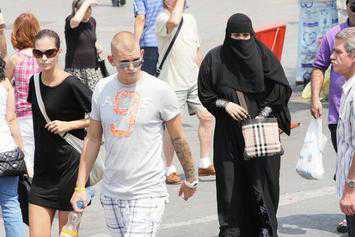

Women in Istanbul

A German notes women treated with respect in Istanbul | Headscarfed or not, they take on open gestures in public identifiable to a European publicAs many as 17 millioninhabitants live in the Turkish metropolis. The social heterogeneity of Turkey is reflected in this crowd of people. Everything is here: in the city centre for example, life runs riot. Alcohol is allowed on the street, transvestites sit in Starbucks, Turkish girls wear mini-skirts. ‘It’s more European than in Europe,’ joke the Turks about the party mile in Taksim, a square leading to the heart of Istanbul. The people here believe in the maxim of the founder of Turkey, Atatürk; a statue of him marks the middle of the square. It’s the alignment of Turkey to the west for prosperity and modernity. The people who I meet on the street think that islam is ‘outdated’ and that European is ‘in’.

Taksim square, Istanbul | Protestors and party people alike meet her, such as to celebrate Michael Jackson’s life (October 2009)

I take a seat on a bus and travel an hour eastwards to an entirely different Istanbul. Tower block after tower block line up as far as the eye can see, where the residential complexes of the Turkish middle class are spread. A Turkish woman explains that arranged marriages are the best marriages, and that women are too sensitive for the world on their doorstep. There are hardly any women to be seen at all on the street. If so, they are veiled, although headscarves are banned in public buildings. In Istanbul, the Turkish women have a trick to still cover their hair: the headscarf stays on but they wear a wig over it. That looks often very strange, but it’s generally accepted. Apart from that, women are treated with a lot of respect. On the bus, free seats always go to female passengers and sometimes even the seats next to them stay free. When I am with my fellow students for a stroll or going out, not one man looks me in the eye or approaches me. I want to smile to the waiter who serves us an ice cream, but I’m completely ignored. The first time it’s weird and I’m a bit hurt. But when I understand that disregarding a woman is a sign of respect, I see it differently. It feels actually pretty good even.

An erasmus semester in Istanbul is an incredibly rewarding experience. You should brace yourself for a little adaptability, but I have to see Istanbul again. It’ll be as soon as next year, as I’ll be writing my master’s thesis about islamic influences in Turkish domestic policy. That kind of research would work better on the ground.

Images: ©Leif; ©Objektivist; ©boublis/ all courtesy of Flickr/ video: ©justuur/ Youtube

Leave a Reply